Magic

Curated by Joy Pepe

This verse, spoken by the Three Witches or the Weird Sisters as they conjure up Macbeth’s doomed fate with a brew of plant and animal parts, are some of the best known in Western literature that express the actions of evil magic contrived by women over the fates of men. Magic explores the bond between witches and magic, and reconsiders the stereotypical wicked intent of witchcraft, whether in its association with the female body and its reproductive ability, its sensuality and sexuality, or its symbiosis with nature’s cycles.

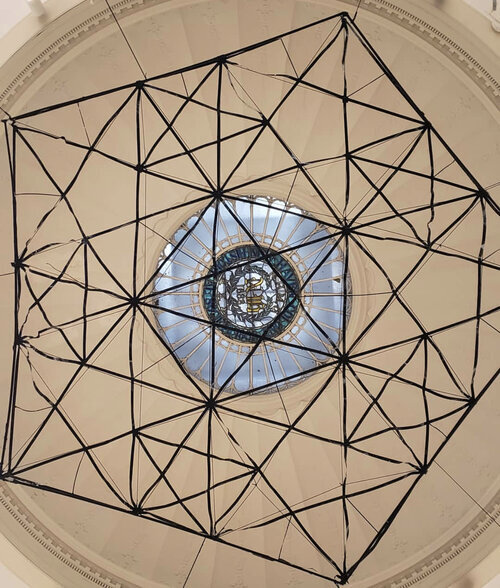

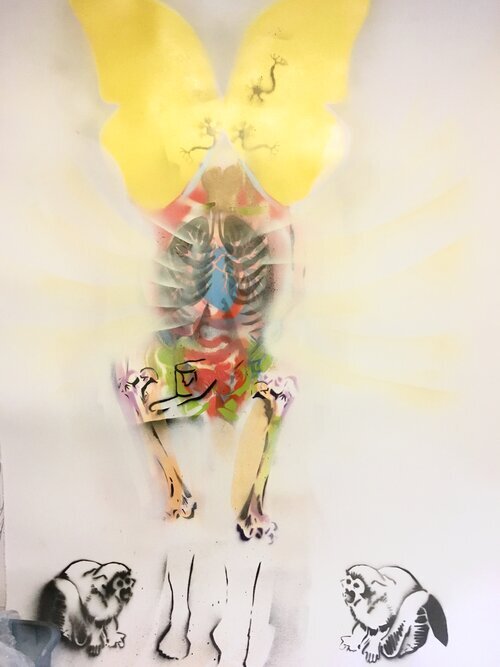

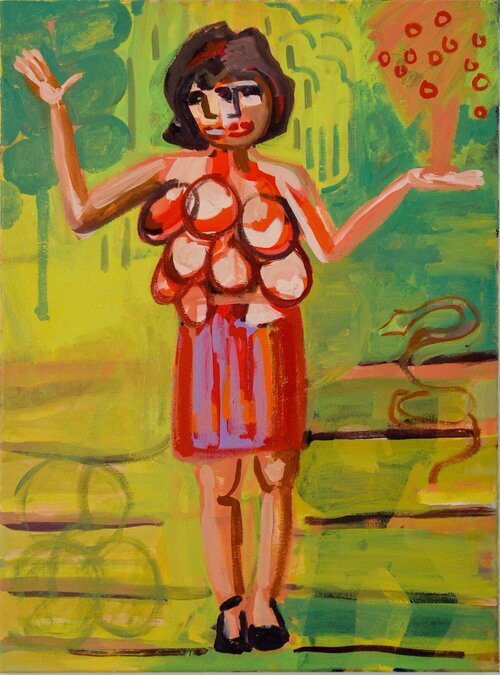

In her site-specific installation, I SAW THE FIGURE FIVE IN BLACK (after Charles Demuth’s I Saw the Figure Five in Gold inspired by a poem by William Carlos Williams), Martha Willette Lewis has composed a delicate, floating pentagram—a magic circle—that responds to the entrance floor motif of the New Haven Historical Society. With magical associations that go back as far as ancient Babylonian and Greek society, the five-point star remains an important symbol to this day, especially for wiccans who use the pentagram to symbolize their faith. With five senses and five fingers on each hand, the artist connects the number 5 with her pentagram and to a history of magical connection. The human aspect of the pentagram is visualized with the top point of the star as the head and the remaining four points as the extended arms and legs. The elements of earth, air, wind and fire coordinate with the limbs, and the head is the spirit center. Humanity’s frailties and strengths endure through the determination of mind and body. The pentagram can also protect those of us who do not fit into mainstream society and culture, who feel bullied and different. It envelops us in a safe collectivity where we no longer feel ostracized. The artist transposes all the negative associations of the pentagram associated with the “devilish” practices of wiccans into an intricate symbol of independence and beauty. The colorful skeleton in Queen of Flight by Alexis Brown arises triumphantly with the morphing of bright yellow butterfly wings onto its shoulders as two hybrid creatures (monkey, dog, cat?) curl up at its dangling tibia, as if worshipful witnesses to its ascendance, much as the apostles at the sarcophagus of the Virgin Mary as her body is supernaturally assumed into heaven. This theme of worship of unworldly beings is continued by Kathy Black’s Artemis of Ephesus, the ancient Greek goddess of fertility, as she depicts a modern woman with short skirt, black shoes, and bobbed brown hair with a torso sprouting multiple breasts with expressive color and brushwork. The modern Artemis of Ephesus may suggest the unspoken burdens that women bear as nurturers, while the repeated double head addresses the search for the “having it all” identity for modern women as they juggle multiple responsibilities as mother and career professional.

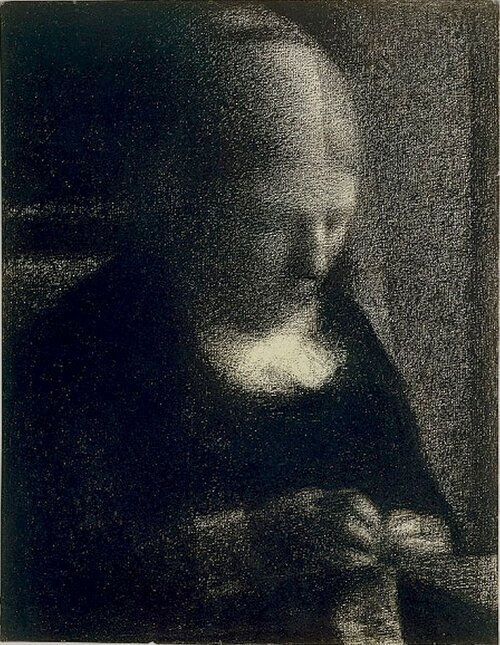

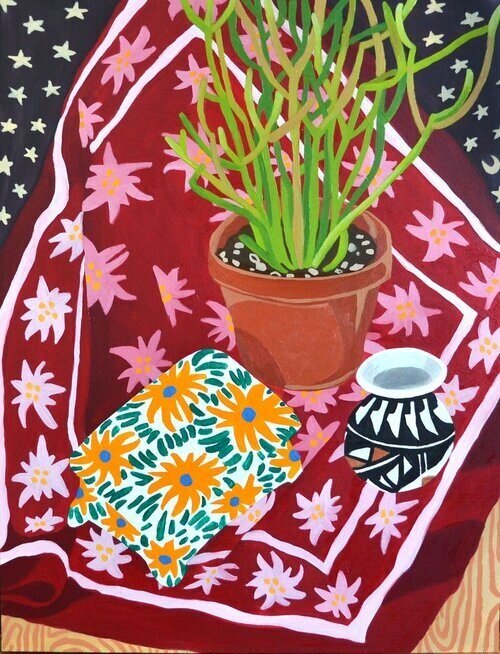

An homage to the exquisite crayon drawings of the Post-Impressionist painter, Georges Seurat, Sheldon Krevit re-presents Seurat’s 1882 drawing (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art) of his mother. Her mature age counters the adoration of youthfulness in modern society. The exact reproduction of the drawing can be placed in the Post-Modernist approach in the early 1980s of artist/photographer, Sherrie Levine, who took a photograph of a reproduction of Walker Evans’s famous Depression era photograph of Allie Mae Burroughs, thereby putting into question the authority and originality of the revered canon of Western male artists. It may also be seen as a re-take of Seurat’s Young Woman Powdering Herself (c. 1889–90, Courtauld Institute Gallery, London). Rather than the vanity of youth, Krevit’s mature woman concentrates on her minute task. Embroidery was one of many learned domestic abilities that defined a woman’s character. And the intricacies of the craft created wondrous designs. However, this attention to her needlework craft can also remind us of the knitting of the imposing and frightening Madame LaFarge in Charles Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities (1859) at the guillotines in revolutionary France in the late eighteenth century, inscribing the names of the dead, even predicting them, in yarn. Domesticity as ritual continues in Grace Hager’s Matissean still-life Red Flowered Bandana and the Moon. The busily patterned surface of florals, stars, and edges of cloth contains a humble terracotta pot holding a stalky plant, a small vessel painted with a geometric design reminiscent of ancient models, a small casket bursting with flowers, and a night sky of stars and small crescent moon peeping out over the bandana’s edge on the central right side. Nature and culture merge on this tabletop, but in the realm of the house as mostly tended to by women and arranged by the artist. The photographed glasses in Bitches Brew 01-04 by Joan Fitzsimmons, compose graceful and elegant still lifes in their singular shapes, filled with a variety of liquids, tinted purple, yellow, green and pink. Are they delightful liqueurs or wine that a hostess would serve while entertaining, or could they possibly be unknown potions or even poison, seemingly innocuous in their distinctive vessels, but concocted into dangerous fluids through her incantations. The house as uncomfortable setting for magical women hovers uneasily in the video by Metha Chantawonga entitled Restriction. A woman in a surgical mask drags a bucket and sponge from a bathroom and scrubs a small section of a wall. We are reminded of the servitude of women to domestic tasks and of their exposure to chemical cleansers with the acidic yellowish greens that dominate the film’s palette. She is restricted visually—the verticals of the architectural elements of doors, windows, mirrors, bannisters entrap her. The chores restrict her actions as she scrubs a small rectangle of wall. But her imagination resounds as she senses life behind the wall, hearing small voices and reverberations and she breaks through to see and hear—a metaphor, perhaps, for the triumph of the female spirit within its own power to break through to selfhood.

The magical object or fetish comes to life in works by Manju Shandler, Scott Schuldt, and Julian Miholics. Shandler’s Primavera (Spring) literally summons Botticelli’s allegorical masterpiece of the 1480s through its title. Spring, assembled here as a multimedia head, is stern and hieratic in its frozen stare downwards, its flowing stringy hair, and low hanging necklace. She approximates a figurehead carved on the bow of a ship. Nature becomes female once again, but not the assured and seductive mistress of the garden of marriage as in the Botticelli, but the relentless goddess of the effortful changing of the seasons. In a departure from the more common feminist reconsideration of witches, Schuldt presents a constructed hybrid creature of diverse materials of wood, hair, antlers, bones—a standing totem of menace and mystery, which, even in its hybrid nature suggests a threatening masculinity. The somewhat monstrous, somewhat comical creatures of Miholics’s Lesbian Werewolves encapsulate the widely fixed image of witches as otherworldly sexualized beings. The lore of werewolves traditionally identifies them as male who sometimes have interspecies, lusty affairs with women. So it is a pointed inversion of the story to have two female werewolves caught in a same sex moment of rousing intimacy. The acid pink color enhances the feminine coding, and the illustrational quality of the drawing gives the scene an unexpected children’s book appeal as the two ‘shewolves’ frolic in Grandma’s garden, little birdies nestle on the fence, a swirly rainbow crosses the night sky, as the moon shines and the stars twinkle. Concluding this discussion of MAGIC, is Emma Windsor’s stop action and animated video, miLK HaRE. The fantasy and terror that fairy tales combine underpin the storyline as a girl enters a ramshackle house while on a forest walk. Within is a warm environment of burning candles, shelves lined with books, bric-a-brac, containers of gooey liquid preserving unidentifiable things, and a milky white stuffed hare, while an actual dead hare hangs from a hook. The girl is drawn to a large book propped on a stand on a table. Upon opening an animated tale is told that includes three sisters who conjure magic potions, environmental deterioration of the forest due to chemical emissions, and a Babadook-like monster who reaches its hand out of the book and pulls the girl into it. At the end, she becomes a black and white photograph within a frame where other children’s pictures reside. Even without her presence, the vile crone lurks as a kidnapper of children, a return to the primal fear of the evil female witch.

— Joy Pepe, curator